Patagonia

National Park

Park Creation

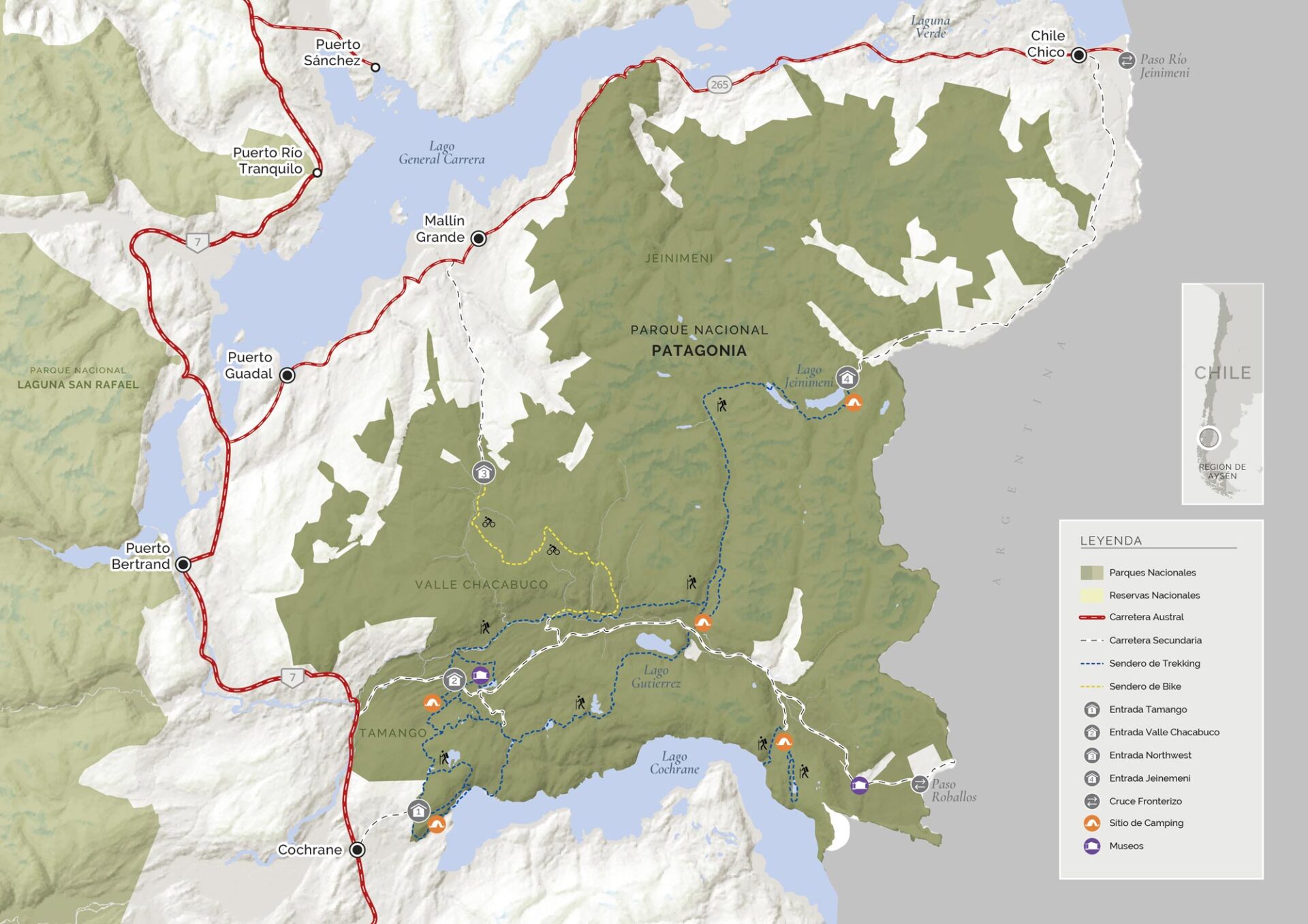

Founded: December 11, 2018

Area: 752,504 acres

Donated area: 206,983 acres

Ecosystem: Patagonian steppe

Estimated carbon sequestration: 102.6 million metric tons

Location: Aysén Region

Patagonia National Park is one of Chile’s most important eco-restoration and rewilding projects. It is made up of the former Tamango and Jeinimeni Reserves, as well as the Chacabuco Valley, which was previously one of the largest livestock farming ranches in the country, before Tompkins Conservation acquired the land and donated it to the state.

The park is home to our wildlife program, led in partnership with Tompkins Conservation and Conaf (Chile’s National Forest Corporation, a part of the Chilean government). This program focuses on the protection of different wild species, including the puma, the condor, the ñandú, and the huemul (South Andean deer), the latter of which is threatened.

History

In 1995, Kristine and Douglas Tompkins visited the Chacabuco Valley for the first time. They quickly saw the urgency of restoring this area to its natural state and ensuring its long-term protection. Conaf had already singled out the area as a conservation priority several years prior, due to its unique ecosystems and biological diversity.

The Chacabuco Valley was previously one of the largest livestock ranches in the region. Established in 1908 by the English explorer Lucas Bridges, and later distributed amongst local families as part of Chile’s 1964 agrarian reforms, the land was expropriated by the military dictatorship under Augusto Pinochet and sold in 1980 to the Belgian landowner Francoise de Smet.

In 2004, Patagonia Conservation, formed by the Tompkins family, acquired the 173,000-acre Chacabuco Valley Estate with the help of various donors. Over the next several years, other properties were incorporated, bringing the total to more than 198,000 acres.

During the following years, several large-scale ecological restoration and rewilding projects were carried out, all with the goal of transforming this former livestock ranch into a national park, which Tompkins Conservation donated to the Chilean state in 2018. This was part of a major donation that also resulted in the creation of four other national parks and the expansion of three more.

Ecological Value

Due to its location in an area where Nothofagus forests give way to eastern steppe, Patagonia National Park encompasses land of notable ecological significance. Adding to this biodiversity are nearby bodies of water, in particular the Baker and Chacabuco Rivers, as well as the expansive Lake Cochrane.

The park’s most important characteristics include the vegetation of the Aysén Patagonian steppe, which can be found here in all its splendor. Other highlights include vast expanses of Andean Patagonian forests in the higher-altitude sectors of the park and along lake-speckled mountain slopes. These forests feature three main species of Nothofagus: lenga, ñire, and coigüe. Rainfall can reach up to eight inches annually, keeping the forests dense and rich in nutrients and fostering their role as home to more than 370 species of vascular plants, which are vital for the survival of fauna who live here.

Patagonia National Park is home to and helps protect one of the highest levels of biodiversity found in Aysén. All the region’s native species––from Andean condors, to guanacos and pumas––can be found in the park. Notably, its large expanses of wild land include habitats that are home to the huemul, an iconic and endangered species found on Chile’s national coat of arms.

Public Infrastructure

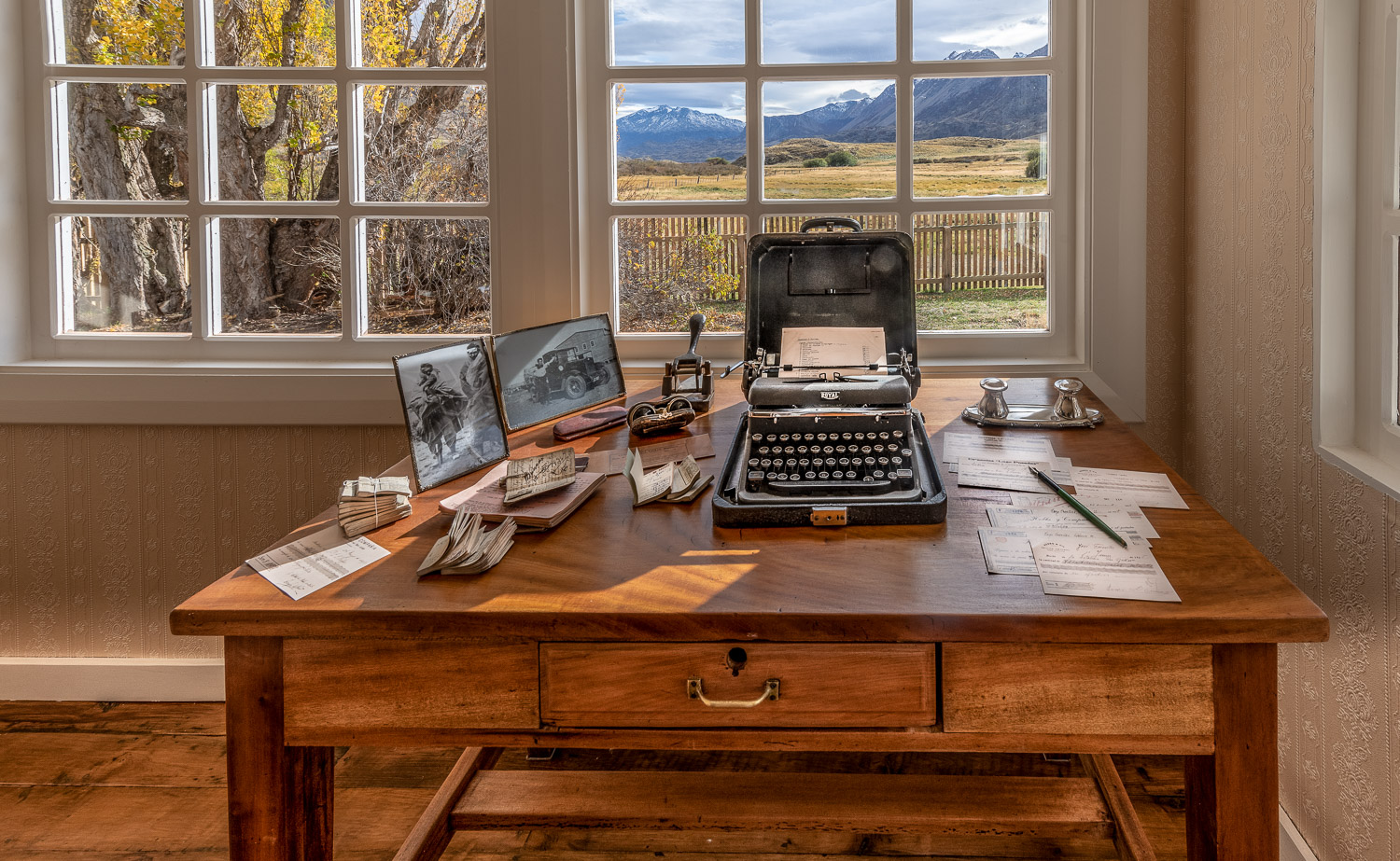

In 2006, with the generous help of various donors, the organization began building the park’s public infrastructure, with a focus on both quality and aesthetics. The buildings were constructed with local materials and recycled wood, in a style inspired by Patagonian architecture, particularly the aesthetic of English landowners who settled here in the 1880s. The project prioritized both durability and sustainability.

Today, the hotel and restaurant are administered by the Chilean company Explora.

The infrastructure includes a lodge, a restaurant, campsites, a visitor center, the Lucas Bridges Home Museum, and a 155-mile-long network of trails.

Patagonia National Park visitor center

Lucas Bridges Home Museum

Wildlife

Wildlife monitoring has been a major part of the complex project of turning a cattle ranch into a conservation area of more than 750,000 acres. Our organization implemented a monitoring program focusing on the park’s iconic species, including the puma, ñandú, and huemul, the latter of which is classified as an endangered species. This program continues today in collaboration with Conaf, and focuses on the preservation and monitoring of these species and their role as indicators of ecosystem health––an ongoing, long-term task.

Our wildlife program has also focused on the recovery of degraded ecosystems affected by overgrazing. Despite still being present in the area, initially many species had very low numbers and density, making their monitoring key to understanding and improving ecosystem health.

The conservation project has featured various phases of active management and rewilding, among them:

- The removal of more than 370 miles of fencing and posts that limited the movement of species, notably the guanaco

- Gradual removal of over 25,000 head of livestock

- Control of environmental threats, especially in priority areas for the huemul

- The active control of invasive species, in particular rosehip and pine

- The protection and monitoring of predator species, including pumas and foxes

- Implementation of measures to mitigate conflicts between predators and sheep farms

- Population reinforcement measures for species with a high risk of local extinction, including the ñandú

Today, this extraordinary territory is the site of reestablished relationships between native species and their ecosystems. Learn more about our wildlife program here.

Patagonian Steppe Restoration

Shortly after the purchase of the Chacabuco Valley Estate in 2004, we began the project of rehabilitating the Patagonian steppe. Eighty years of overpopulation of sheep and cattle in these valley’s pastures, which are not suitable for livestock farming, had left patches of invasive species, weakened grasses, and infertile land. The gradual removal of livestock and fencing, along with the planting of native coirón, helped to restore the steppe.

Under the direction of a restoration ecologist, we collected soil samples to guide the development of management plans in different areas of the park. Volunteers collected seeds of native grasses, including coirón, and helped to reseed damaged areas, carrying out one of the most extensive grassland restoration projects in the world.

Community Programs

The long-term fate of protected areas depends largely on the people who live near them. With this in mind, we developed various initiatives to connect local communities with the natural heritage around them.

Outdoor Education Program

As part of the creation of Patagonia National Park, we launched this innovative initiative to bring the community closer to their park. The Outdoor Education Program was established in 2014 with the support of a North American environmental foundation, and it funded park visits for hundreds of children and young people from Cochrane and Chile Chico, where they learned about their local ecosystems.

Over the past eight years, students from the nearby Austral Lord Cochrane School have had the chance to hike and camp in the park, and participate in the huemul, condor, and ñandú conservation programs. This outreach has had a positive impact on the community, and is now managed locally by the school and a team of environmentalists. It was highlighted by the Chilean Ministry of Education as an example of best practices.

Route of the Huemul

Over the course of a decade, we sponsored the Route of the Huemul, a two-day community hike that fostered local awareness of the area’s exceptional ecology and knowledge of this threatened species’ habitat.

During its initial years, the hike culminated in a large barbecue to celebrate participants’ efforts. Now, the activity is a tourist attraction run by the Cochrane Municipality, drawing more than 100 enthusiasts to the area annually.

Volunteer Program

This transformation of a livestock ranch into a national park was supported by an extensive volunteer program, including the participation of 750 people from Chile and around the world. These volunteers helped with the removal of invasive species like hemlock and rosehip, as well as the removal of more than 370 miles of fencing, which made it possible for wildlife to roam freely throughout the area.

Volunteer work was also key to controlling invasive pine trees. More than 12,000 were removed from the huemul’s habitat. Similarly, volunteers helped dismantle old buildings and other infrastructure not needed for park operation, saving recyclable materials for other infrastructure projects.

Volunteer work has continued over time, including activities like research collaboration and work in the ñandú reproduction center.

The park’s organic garden, which was tended throughout the entire construction period, also received volunteers from around the world, many of whom came to learn about biointensive agriculture and the challenges of farming and gardening in a region where 80% of consumed food is imported from the northern regions of the country. Our garden supplied fresh food for workers and for the park’s restaurant, and was notable for its balance of productivity and aesthetic beauty. The garden produced more than 3.5 tons of food annually, while taking up very little space and using only compost from household and restaurant waste. We grew more than 35 varieties of vegetables, along with 20 species of flowers and medicinal herbs.

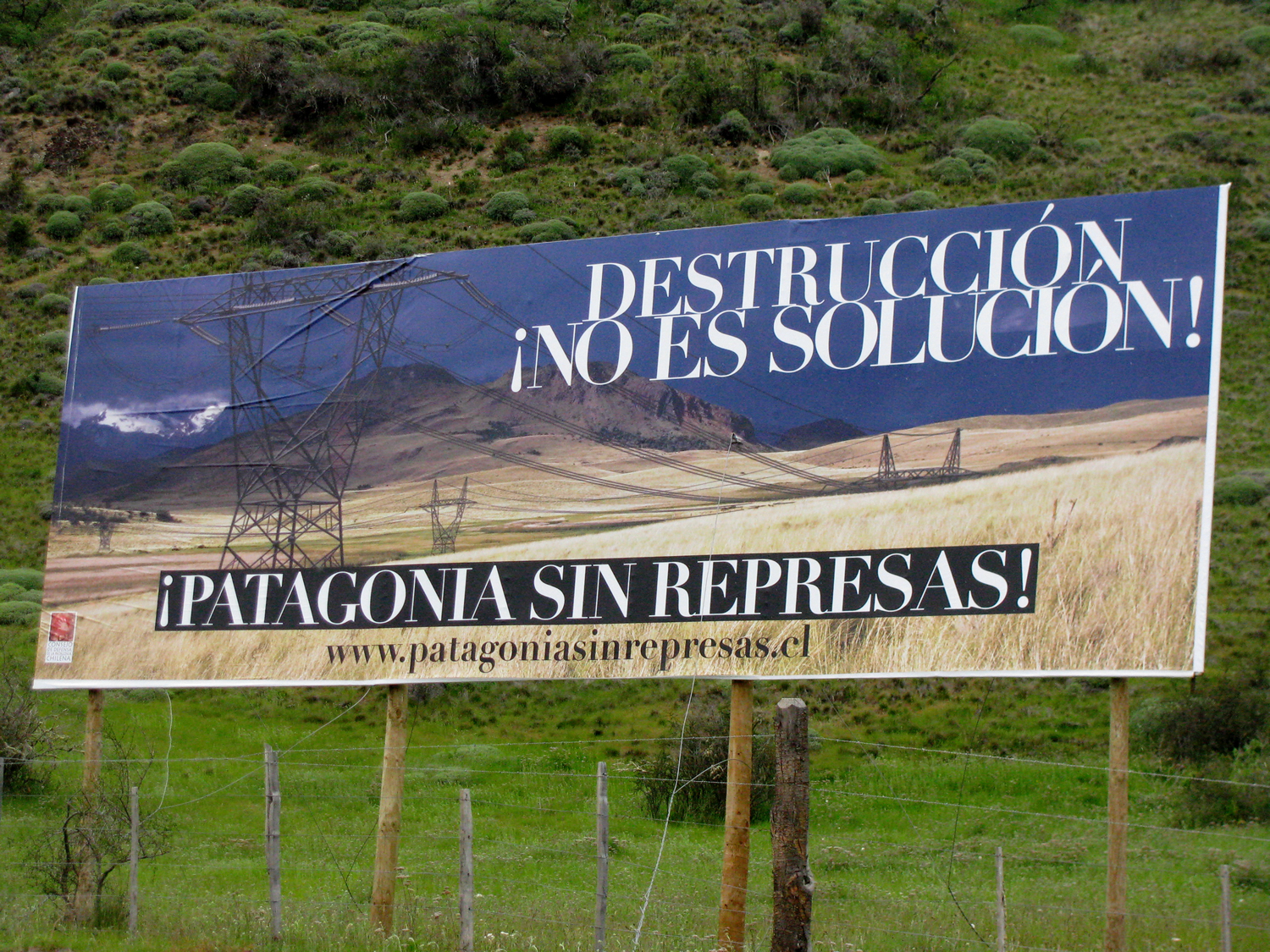

Campaigns

In addition to the creation of parks, we have also developed various campaigns helping to defend these territories and promote locally-based projects that prioritize conservation and beauty. As part of these efforts, in 2007, while building Patagonia Park, we joined the Patagonia Sin Represas (Patagonia Without Dams) coalition. This alliance included more than 80 NGOs, as well as support from individuals on the local and national level, and we were successful in our goal of stopping the HidroAysén dam project. In another effort, our campaigns have helped to promote the Route of Parks of Patagonia as a scenic destination, featuring highlights like the roads through Pumalín Park and Patagonia Park, which stand out both for their beauty and their biodiversity. We worked collaboratively with the Chilean Transit Authority through workshops and data collection to create Chile’s first Scenic Route Instructional Document, launched in 2017. The document defines and clarifies concepts, criteria, and procedures that help to identify and select Transit Authority routes that possess scenic tourism potential, aiding in these routes’ strategic management.