Pumalín Douglas Tompkins

National Park

Park Creation

Founded: February 28, 2018

Area: 994,332 acres

Donated area: 724,854 acres

Ecosystem: Temperate rainforest

Estimated carbon sequestration: 229.3 million metric tons

Location: Los Lagos Region

Pumalín means “watery place” in the language of the Huilliche people (“Pu” is place, and “malín” is marshland or flooded area). This spot is a beautiful mosaic of ancient forests that abruptly give way to fjords, rivers, granite walls, glaciers, volcanoes, waterfalls, and lakes suspended in mountain heights. It’s also home to 25% of the thousand-plus-year-old alerce trees (Fitzroya) still growing in Chile today. The temperate, or Valdivian, rainforest was untouched by the ice that covered most of this region 14,000 years ago, which kept these unique forests and their many endemic species protected for millennia. Here, Douglas Tompkins began carrying out his vision of conserving Chilean Patagonia––a vision still alive today in the Route of Parks of Patagonia.

History

In 1989, Douglas Tompkins saw this area’s ancient, wild alerce forests for the first time and began looking for ways to help preserve them. In 1991, he bought around 41,500 acres in the Reñihué Valley, along the Comao Fjord. He quickly realized that in Reñihué, most nearby land belonged to absentee landowners whose families had acquired the plots in the 1920s during a boom in logging industry speculation. Tompkins and his wife and fellow conservationist Kristine Tompkins settled in the area permanently and formed Tompkins Conservation, through which they began acquiring around 692,000 acres of neighboring land, starting the long process of creating Pumalín Park. This land was subsequently donated to Pumalín Foundation, a Chilean NGO created to run and preserve the private, public-access park, while preparing for the final goal: donating the land to the state so that it could be protected as a national park.

The creation of Pumalín Park was controversial. There hadn’t previously been much of a philanthropic culture in Chile in the environmental area. This lack of tradition in environmental philanthropy led to suspicion about the project’s––and its North American leaders’––real goals. For this reason, the organization sought the official label of Natural Sanctuary for Pumalín, to help assuage any fears about the foundation’s intentions, as well as adding to the protection of this land, which was still private at the time. In 2005, this interim goal was achieved and Pumalín Park was declared a Natural Sanctuary by then-president of Chile Ricardo Lagos.

In 2009, Tompkins Conservation began working on the proposal for re-designating the area as a national park, alongside ten other proposals for the creation or expansion of other national parks throughout Chile. In 2011, the organization attempted to donate these areas in a multi-project process; however, these donations were nearly all rejected on account of the creation of protected areas being considered synonymous with taking away potentially productive land. At that point, it was possible to move forward only with one project: Yendegaia National Park. In 2015, a new proposal was presented to then-president Michelle Bachelet, which included multiple conservation projects, all united under the Route of Parks of Patagonia. Shortly thereafter, Douglas Tompkins passed away in an accident while kayaking on Lake General Carrera.

In 2018, in an unprecedented public-private partnership, President Bachelet and Kristine Tompkins succeeding in making this vision a reality, formalizing the largest private land donation to a state in the history of the world (around 996,000 acres from Tompkins Conservation Chile), which was combined with the incorporation of previously state-owned land and the reclassification of national reserves to create Pumalín Douglas Tompkins National Park, along with four other brand-new parks (Melimoyu, Cerro Castillo, Patagonia, and Kawésqar), as well as the expansion of three parks (Hornopirén, Corcovado, and Isla Magdalena). With this, the Route of Parks was born.

Ecological Value

Pumalín is part of the Andes Mountains. The mountains descend to the coastline, sculpting narrow valleys, deep fjords, and islands. This area, filled with lush and intricate nature, receives an average of 240 inches of precipitation annually, giving life to evergreen forests that, in some places, hang from cliffs plunging down into the fjords.

Half of Pumalín Douglas Tompkins National Park features an incline of greater than 60%. Just a small fraction of the park has semi-flat terrain, mostly in valleys. These steep inclines made the installation of settlements and roads extremely difficult, one of the reasons the area remained relatively untouched and is home to pristine, dynamic ecosystems to this day.

This temperate rainforest ecoregion plays a crucial ecological role. The Andes to the east and the Pacific Ocean to the west and south make the Valdivian Rainforest a biogeographic island with an enormous number of endemic species. It’s listed as one of the top 34 areas for biodiversity on the planet, with the presence of more than four thousand vascular plants––half of which cannot be found anywhere else on Earth. Fauna highlights include the chucao and hued hued birds, the pudú deer, Darwin’s frog, the otter, and the guiña cat, all of which live alongside the towering alerce trees and the ciprés de las guaitecas (Pilgerodendron), the southernmost conifer in the world. Pumalín is home to old growth forests that have been flourishing for thousands of years in the same spot, in refuges formed by the last ice age 14,000 years ago.

Public Infrastructure

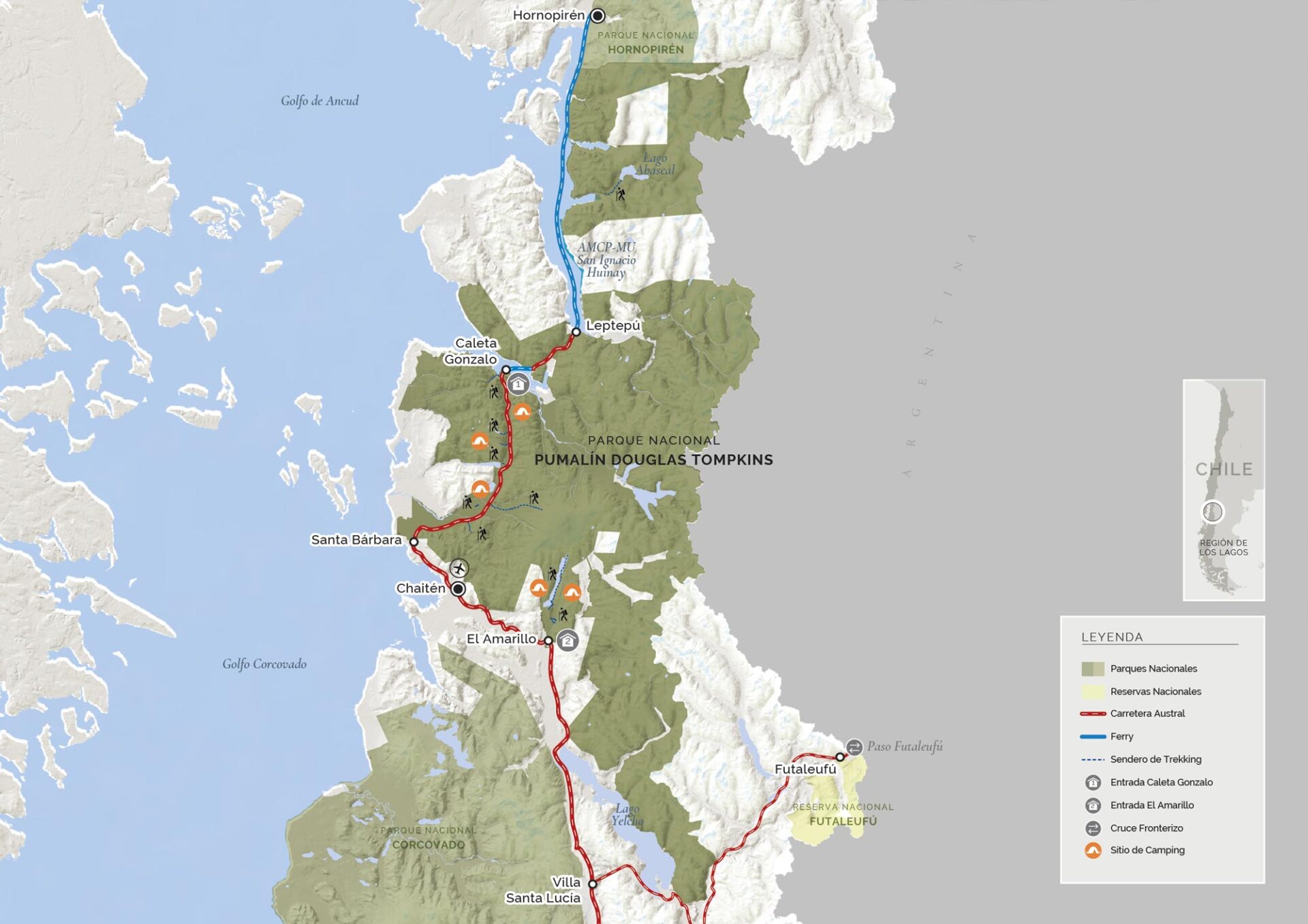

Pumalín Douglas Tompkins National Park receives thousands of visitors each year. Its campsites are distributed throughout 50 miles from north to south, along with cabins and a café in the Caleta Gonzalo sector. Its 11 different trails offer more than 45 miles of hikes, from short strolls through day-long treks, and feature various lookout points, information centers, picnic areas, and signage, all of which was donated to the Chilean state along with the land.

The infrastructure was designed with great attention to detail, with the goal of minimizing impact and offering a quality experience to each visitor. Along with Patagonia National Park, Pumalín serves as a model park, with special emphasis on the visitor experience, ensuring a cohesive, traditional architectural style and aesthetic, using local materials and high-quality craftsmanship.

The park is now run by Conaf, a part of the Chilean government. You can find more information about visiting at rutadelosparques.org and conaf.cl (in Spanish).

Eco-Restoration

During the park creation process, we also carried out various eco-restoration efforts. For 15 years, this included a native forest restoration project, using the native species nursery garden Alerce 3000 as home base. Located in Vodudahue, this project was the first of its kind, and it led to the production of more than 160,000 native trees, all of which were planted in the park. This included 45 thousand alerces, 23 thousand ciprés de las guaitecas, and more than 27 thousand ciprés de la cordillera.

Beginning in the year 2000, the project also included the propagation of different species, increasing production to more than 60 thousand plants annually. Seeds were collected in the reforested areas, helping to carry on this spot’s unique genetic legacy. These efforts led to the restoration of nearly 400 acres of forest with 23 native species, 60% of which were alerce, ciprés de las guaitecas, and ciprés de la cordillera, prioritizing reforestation in areas where there had been human settlements, logging, and agriculture that had long degraded the ecosystem.

The project also helped to promote the reforestation of native species throughout the region, becoming one of the main providers of native plants for Conaf’s urban planting program in Los Lagos. The initiative was taken over by a new owner at the end of 2015, with the sale of the Vodudahue farm.

Another important restoration project during the park’s creation was fixing eroded roads. This included the roadsides, with development of specialized techniques for cleaning the borders of the public roads both in and around the park. These efforts led to improvements on the road shoulders that helped to create a new standard that government organizations have now begun incorporating into their transportation contracts. Our team worked closely with Chile’s Public Works Ministry to advise on similar aesthetic and visual regulations for the creation and updating of roadways, which help to bolster local pride as well as ecotourism.

In 2008, the eruption of the Chaitén Volcano brought new challenges to Pumalín. The El Amarillo sector suffered the most damage, with the area covered in several feet of volcanic ash. The park was closed to the public between 2008 and 2010, which allowed us to focus on the huge task of repairing damaged infrastructure, as well as supporting the natural spaces’ recovery. We carried out various furrowing processes in the ash-covered fields. This helped the rain gradually wash away the ashes, until a small enough amount remained that they could be mixed into the soil.

The eruption caused the rivers to change their course. Flooded roads needed repairs and rebuilding, along with campsites that needed excavating and repairing. Finally, we also built a new information center and administration office in El Amarillo in 2013, replacing the damaged ones previously located in Chaitén.

Communities

Fostering local pride

The creation of Pumalín Douglas Tompkins National Park wasn’t just about the conservation of this valuable territory. It was also about inspiring local communities, promoting respect for nature, and fostering local pride.

With this latter aim in mind, the organization began the El Amarillo Beautification Project, a community revitalization initiative in this small town 15 miles south of Chaitén, at the southern entrance to Pumalín Park. The goal of the project was to improve quality of life for locals as well as stimulating small-scale tourism. Efforts included fixing up homes’ facades, local gardens, and public spaces, all to increase local pride and highlight the natural beauty and heritage of this special place. After the 2018 eruption of the Chaitén Volcano, this project became even more urgent.

We worked together with locals to remodel, paint, and renovate the facades of more than 30 homes, including the church and school. We installed fences and planted trees and flowers to improve the gardens and outdoor spaces. The project also included building a new supermarket called Puma Verde and a local gas station, as well as carrying out the beautification and renovation of public infrastructure, such as public transit stops, roads, sidewalks, landscaping, and signage. Today, El Amarillo is one of the most charming stops along the Carretera Austral, and its community members are known as active and empowered advocates for their natural heritage. For more information about the project, download the El Amarillo booklet here.

The Reñihué Folklore Festival was another initiative to help promote local pride. For nine years, Douglas and Kristine Tompkins invited more than 400 people to their farm annually for this three-day festival. People––including musicians, local leaders, and other attendees––arrived by boat from nearby towns to enjoy the music, food, and dance. The festival also included forums about the future of the local culture and identity, and the menu featured typical fare like curanto and barbecues, among other traditional dishes.

Another part of the community outreach program was the creation of various rural schools for the children of Tompkins Conservation staff. Over 25 years, the foundation directly employed more than 1,700 people, not including the volunteers and external contractors who also played an important part in our story. Given the projects’ remote locations, we knew we’d need to have our own schools for employees’ children. In Reñihué, Pillán (Pumalín Douglas Tompkins National Park), and the Chacabuco Valley (Patagonia National Park), we ran primary schools that followed the Ministry of Education’s official programs. In addition to completing the standard coursework, students also attended outdoor education classes to learn about biodiversity, gardening, and folklore. This helped promote the next generation’s earth-centered ethics and their connection with the land.

During the creation of Pumalín Park, our team along with Tompkins Conservation collaborated with the Ministry of Public Lands to regularize the land titles in the buffer areas near and around the park. This project arose as the result of a review of these properties and their boundaries. Ten years’ of work on this project helped to regularize all pending titles, which aided in the stability and quality of life of the park’s neighboring residents.

Model farms

The Pumalín project was conceived primarily as a large-scale conservation effort. Model agricultural fields adjacent to the conservation area acted both as a buffer zone for this conservation and a place to situate park ranger stations. These fields provided areas for carrying out activities such as animal husbandry, wool crafts, cheese and honey production, and more. They served as a model for how a diversified agrarian economy, adapted to local conditions, could help to provide food and economic opportunities to locals, while at the same time protecting the environment.

These farms––Reñihué, Pillán, and Vodudahue––were sold in 2015 to new owners who pledged to continue this vision of conservation-based production.

Campaigns

During the course of our work to create Pumalín Douglas Tompkins National Park, we also supported various environmental campaigns to defend this territory and ensure its long-term conservation. Highlights included a campaign against salmon farming [LINK A ACTIVISMO], a campaign to increase Palena’s connectivity [LINK A ACTIVISMO], and an initiative that sought to formalize the Carretera Austral’s status as an official scene route.

Part of this activist work also included the 2019 publishing of Pumalín Douglas Tompkins National Park, which celebrates the creation of this protected area––the most emblematic project of our foundation during these nearly three decades of work. The book includes photographs by the outstanding nature photographer Antonio Vizcaíno and contributions from various people who played a role in the park’s creation, including former Chilean presidents Ricardo Lagos and Michelle Bachelet.

Scenic Route

In 2012, we launched a campaign encouraging the government to designate the entire Carretera Austral an official scenic route. The goal of this project was to improve the road’s aesthetic quality, promote tourism, and stimulate local economies.

During President Ricardo Lagos’s administration, the first proposal for a scenic route designation in the history of Chile was submitted.

Between 2012–2013, the Tompkins Conservation editorial team produced an English- and Spanish-language book called The Carretera Austral: The Most Spectacular Route in South America, part of a campaign to help spread the word about this magnificent route.

We worked collaboratively with the Chilean Transit Authority through workshops and data collection to create Chile’s first Scenic Route Instructional Document, launched in August 2017. The document defines and clarifies concepts, criteria, and procedures that help to identify and select Transit Authority routes that possess scenic tourism potential, aiding in these routes’ strategic management.

Today, the Carretera Austral is an integral part of the Route of Parks of Patagonia, recognized worldwide as one of our planet’s most beautiful conservation routes.

Palena, province of parks

Well-designed, free posters are a high-impact tool for activism campaigns. From 2005 to 2010, we led a very effective distribution effort to reinforce a regional identity rooted in the value of nature. Douglas Tompkins helped design a series of posters featuring beautiful photos of Pumalín Park and other wild areas, alongside the slogan “Palena: province of parks.” The goal was to communicate that in Palena, visitors can find some of the most beautiful and most well-protected places in Chile. This widely-distributed poster series helped build local pride in the ecological and cultural attributes of Palena and Northern Patagonia. You can download some here.

For more information about the park click here